Why you’re busy but going nowhere — and the 3-question audit that fixes it.

It’s Friday at 4pm.

You look at your calendar for the week. Back-to-back meetings Monday through Thursday. Slack threads answered. Emails cleared. A dozen small fires extinguished. You were busy every single hour.

But when you try to name what you actually built this week — crickets.

In 2009, Paul Graham wrote an essay that explained this feeling better than anyone. He called it “Maker’s Schedule, Manager’s Schedule.”

His argument was simple: there are two fundamentally different ways to use time. Managers operate in one-hour blocks — meetings, check-ins, decisions. Makers need half-day chunks to do real work. Writing, building, thinking — you can’t do any of it in fragmented 45-minute windows between calls.

“A single meeting can blow a whole afternoon,” Graham wrote, “by breaking it into two pieces each too small to do anything hard in.”

That was 16 years ago. The problem has gotten worse.

Meetings per person have more than doubled since 2020. Nearly 70% of workers say they don’t have enough uninterrupted focus time. And now AI is generating more output than ever — but output toward what, exactly?

That’s the question most ambitious professionals still can’t answer on a Friday afternoon.

The Calendar Trap

The numbers paint a pretty bleak picture.

According to Asana’s research, knowledge workers spend 58% of their time on “work about work” — coordination, status updates, communication overhead. Not the skilled work they were actually hired to do. That adds up to 103 hours per year in unnecessary meetings and 352 hours just talking about work.

Gloria Mark at UC Irvine has spent decades studying digital distraction. Her finding: it takes roughly 23 minutes to fully refocus after a single interruption. Meanwhile, our average attention on any given screen is about 47 seconds before we shift to something else.

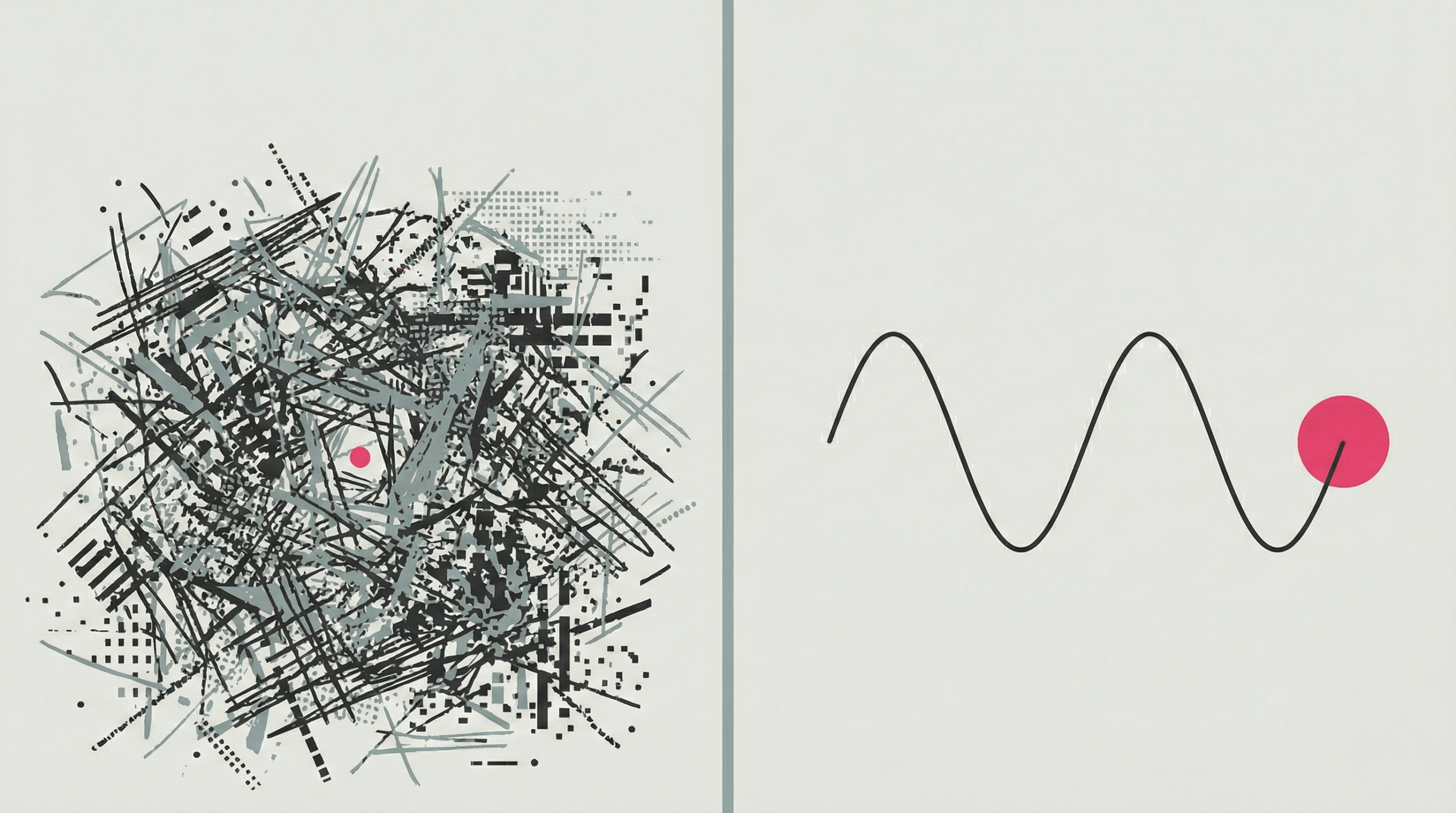

Put those two facts together. Your calendar is chopped into fragments. Each fragment triggers a context switch. Each switch costs you 23 minutes of refocus time you don’t have. And between the fragments, you’re bouncing between screens every 47 seconds.

Your calendar looks full. Your output log tells a different story.

I’ve lived this. Every manager has — because the truth is, you rarely have full ownership of your schedule. You’ve got meetings wedged between attempts at deep work, and neither gets your best. At Staffbase, we tried something that helped: a company-wide no-meeting Friday. It wasn’t perfect, but it carved out space for the thinking that meetings tend to crowd out. The real lesson was simpler, though — you need blocks in your week where you can just think. Without them, you’re reacting, not building.

You Don’t Have a Productivity Problem

Here’s where it gets uncomfortable.

Most people try to solve this with better time management. A new app. A different calendar system. Another productivity framework promising to squeeze more from less.

But the problem isn’t efficiency. It’s direction.

Research from Columbia Business School found that in modern American culture, a busy and overworked lifestyle (AKA hustle culture) has become an aspirational status symbol. People who signal that they’re constantly working are perceived as higher status and more competent. As one summary put it: “Our time has become the new diamond rings and Gucci handbags.”

So we wear busyness like a badge — and it feels productive. But Kellogg School researchers found that when workload is high, people systematically choose easier, simpler tasks first. It gives short-term relief. You tell yourself, “oh I got some shit done.” And it erodes long-term performance. As one researcher put it: an employee who finishes a lot of easy tasks each day may seem productive — but that’s not ultimately what matters.

Tim Ferriss asks the best question I’ve found for this in The Four Hour Work Week: “Being busy does not always mean real productivity… Are you inventing things to do to avoid the important?”

That question stings because the answer, for most of us, is yes.

You don’t have a productivity problem. You have a clarity problem.

More tools won’t fix it. More hours won’t fix it. The scattered feeling isn’t about doing too little — it’s about not knowing what matters. Without that clarity, every input feels equally urgent. Every task gets the same weight. And you end the week exhausted, with nothing to show for it that you actually care about.

And the worst part is you can feel it when you don’t have clarity. There’s this massive friction, this friction of uncertainty. It’s not laziness, it’s not burnout; it’s the anxiety of not knowing. Not knowing whether the thing you’re working on matters, not knowing what the future brings. And it’s this friction that drains your battery. It’s exhausting in a way that no productivity system can fix. The only fix is getting clear on the way forward and on the things that you have control over.

Why AI Without Clarity Is Dangerous

And then there’s AI.

AI is no longer just about prompts. With tools like Claude Code and Cowork, AI is handling more of the how — the execution, the building, the producing. Which means what matters most now is the what and the why. Your clarity. Your context. Your direction.

A Harvard Business School experiment with 758 consultants at BCG found that AI users completed 12% more tasks, 25% faster, at 40% higher quality — but only on tasks that were well-defined and within AI’s strengths. On ambiguous tasks outside AI’s frontier? Consultants with AI access were 19 percentage points less likely to reach the right answer. They produced more, faster — but it was wrong.

AI doesn’t create clarity. It scales whatever clarity — or confusion — is already there.

Without knowing what matters, AI just helps you do the wrong things faster.

How Greg McKeown Turned a Hospital Room Into a Career Philosophy

So how do we fix this? Enter Greg McKeown. Author of Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less. Greg understands these challenges.

The day after his daughter was born, McKeown left his wife and newborn in the hospital to attend a client meeting. His manager told him the client would respect him for the commitment. But the clients’ faces told a different story — they mirrored McKeown’s own discomfort with the choice he’d made.

“If you don’t prioritize your life,” McKeown later wrote in Essentialism, “someone else will.”

That moment became the catalyst for everything McKeown built afterward. He left his company, returned to Stanford, and wrote the book that would reframe how millions think about focus and intentionality.

McKeown’s insight wasn’t about doing more. It was about doing less — deliberately. Steve Jobs operated from the same principle when he returned to Apple and cut 70% of the product line, reducing everything to four products in a simple quadrant. “Deciding what not to do,” Jobs said, “is as important as deciding what to do.”

Clarity isn’t a personality trait. It’s a practice — a set of questions you return to daily.

Here’s the audit I use.

The 3-Question Clarity Audit (5 Minutes, 3 Time Horizons)

Three questions. Three time horizons. Five minutes.

1. “If I could only work 2 hours today, what would I do?”

This question strips away everything except what actually moves the needle. Most people can’t answer it instantly — and that pause tells you everything about your clarity.

The goal isn’t to only work 2 hours. It’s to know, at any given moment, what the one thing is. As Craig Ballantyne puts it: “The best to-do list sticks to a handful of very specific, actionable, and non-conflicting items. Schedule your number one priority first.”

Do this now: Open a blank page. Write down the ONE thing that would make today a win. Not three things. One. Now protect the first 90 minutes of tomorrow morning for it — before the inbox opens.

2. “What am I avoiding by staying busy?”

Busyness is the most socially acceptable form of avoidance. There is always a hard thing hiding behind the easy things. The strategy conversation you’re dodging. The project you need to kill. The feedback you need to give.

Steven Pressfield calls this force the Resistance — and it’s strongest precisely when the work matters most. It doesn’t show up as laziness. It shows up as busyness. You’re not procrastinating. You’re productively procrastinating — and there’s a big difference.

Do this now: Write down the one thing you’ve been “meaning to get to” for weeks. That’s your answer. Block 30 minutes for it tomorrow morning. Not next week. Tomorrow.

3. “What does my perfect Tuesday look like?”

Not your dream vacation. Not your peak moment. Your ideal ordinary day.

Tuesday — the most unremarkable day of the week. It’s not Monyay, certainly not TGIF, and not hump day yet. If you can describe it in vivid detail (what time you wake up, what you work on first, who’s around you, what you say no to), you have a compass. If you can’t, you’re navigating without one.

Psychologist Martin Seligman’s research on “prospection” shows that the mind constantly generates representations of possible futures — and that behavior is guided by evaluating those imagined futures. When your picture of the future is vague, your present choices are scattered. When it’s concrete and specific, your mind has something to organize around.

The Perfect Tuesday isn’t a vision board exercise. It’s a compass calibration.

Do this now: Describe your perfect Tuesday in 200 words. Be specific: What time do you start? What’s the first thing you work on? Who’s around you? What’s not on the calendar? Read it back. Does your current week look anything like this?

What to Ask Yourself Next Friday at 4pm

Think about next Friday at 4pm.

The question isn’t “What did I accomplish this week?” That’s an output question — and it keeps you on the hamster wheel.

The better question: “Did I spend this week on what actually matters?”

If you can’t answer that with conviction, the problem isn’t your calendar. It’s not your tools. It’s not your time management system.

It’s your clarity.

And clarity isn’t something you find once and keep forever. It’s something you practice — daily, weekly, deliberately. The 3-Question Audit takes five minutes. The cost of skipping it is measured in years.

Try it tomorrow morning. Before the meetings start. Before the inbox opens. Just the three questions.

That’s where everything changes.

A: Most ambitious professionals confuse activity with progress. Research shows knowledge workers spend 58% of their time on coordination and “work about work” — not skilled output. The fix isn’t better time management. It’s getting clear on what actually matters so you can direct your energy intentionally.

A: A productivity problem means you know what matters but can’t execute efficiently. A clarity problem means you don’t know what matters — so every task feels equally urgent and you end the week exhausted with nothing meaningful to show. Most people treat clarity problems with productivity solutions, which makes it worse.

A: Use the 3-Question Clarity Audit: (1) “If I could only work 2 hours today, what would I do?” strips away everything except what moves things forward. (2) “What am I avoiding by staying busy?” exposes the hard thing hiding behind easy tasks. (3) “What does my perfect Tuesday look like?” gives you a compass for daily decisions. Five minutes, three time horizons.